Explore the fascinating anatomy of honey bees in this detailed guide. Learn how their body structure, sensory organs, wings, and internal systems are uniquely adapted for pollination, communication, and hive survival.

Honey bees (Apis mellifera) are some of the most complex and efficient insects in the animal kingdom. Their anatomy is perfectly adapted for tasks like foraging, defending the colony, producing honey, and communicating through dances. Understanding honey bee anatomy is essential for beekeepers, entomologists, and nature lovers alike.

This guide breaks down the honey bee’s body structure—from the stinger to the brain—revealing the biological marvel that powers the hive.

The Three Main Body Parts of a Honey Bee

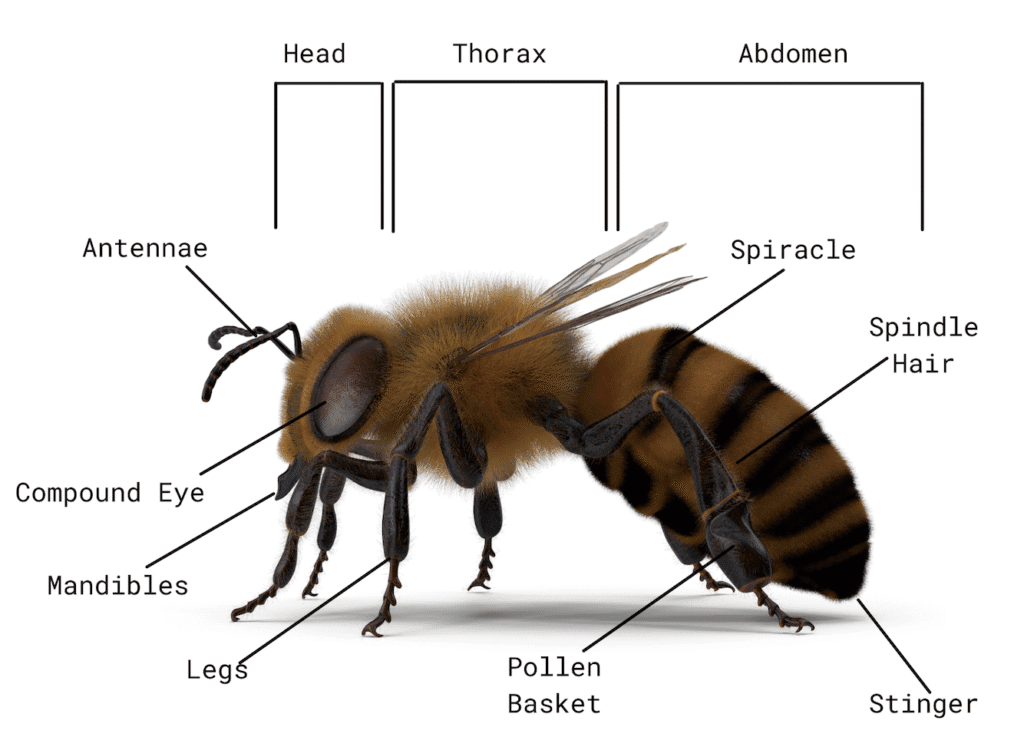

Like all insects, honey bees have three major body segments:

1. Head

The head is the bee’s control center, housing its brain, sensory organs, and feeding structures.

- Compound Eyes: Large, multi-faceted eyes that detect color, UV light, and motion—essential for navigation and foraging.

- Ocelli: Three small simple eyes on top of the head that detect light intensity and orientation.

- Antennae: Key sensory organs used to detect pheromones, vibrations, taste, and smell.

- Mandibles: Strong jaws used for chewing, defending, and manipulating wax.

- Proboscis: A long, straw-like tongue used for sucking up nectar and water.

2. Thorax

The thorax is the bee’s powerhouse, responsible for movement and wing function.

- Wings: Two pairs of wings (forewings and hindwings) are connected with tiny hooks called hamuli, allowing synchronized flight.

- Legs: Three pairs of jointed legs, each adapted for specific functions:

- Front legs: Equipped with an antenna cleaner.

- Middle legs: Used for grooming.

- Hind legs: Feature a pollen basket (corbicula) for collecting and transporting pollen.

- Flight Muscles: The thorax contains powerful muscles that allow bees to fly up to 15 mph and beat their wings 200 times per second.

3. Abdomen

The abdomen houses most of the bee’s vital internal organs.

- Digestive System: Includes the honey stomach (crop), midgut, and hindgut.

- Honey Stomach (Crop): Temporary nectar storage before transferring it to the hive.

- Wax Glands: Present in worker bees; produce wax for building honeycombs.

- Stinger: Female worker bees possess a barbed stinger used for defense. It is connected to venom glands.

- Spiracles: Small openings used for respiration.

- Reproductive Organs:

- Queen: Fully developed ovaries.

- Drone: Large testes.

- Worker: Sterile or underdeveloped reproductive organs.

Internal Systems of the Honey Bee

1. Nervous System

- Honey bees have a highly developed nervous system with a small but efficient brain.

- Responsible for learning, memory, dance communication, and complex behavior.

2. Circulatory System

- Bees have an open circulatory system.

- Hemolymph (insect blood) is pumped by a dorsal heart and carries nutrients—not oxygen.

3. Respiratory System

- Air enters through spiracles and travels via tracheal tubes directly to tissues.

- Bees do not have lungs.

4. Digestive System

- Converts nectar into honey.

- Includes enzymes like invertase that break down sugars.

5. Excretory System

- Malpighian tubules filter waste from hemolymph into the hindgut.

- Waste is expelled through the rectum.

Caste-Based Anatomy Differences

Honey bees are eusocial insects with three castes: queen, workers, and drones. Each has unique anatomical adaptations.

| Feature | Queen Bee | Worker Bee | Drone Bee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Largest | Medium | Large & stout |

| Wings | Smaller than body size | Proportionate | Larger wings |

| Stinger | Smooth (can sting multiple times) | Barbed (can sting once) | None |

| Reproduction | Fully fertile | Sterile | Fertile (mates with queen) |

| Legs | No pollen baskets | Equipped with pollen baskets | No pollen baskets |

Interesting Anatomical Adaptations

- Hairy Eyes & Bodies: Help collect pollen during foraging.

- Pheromone Detection: Antennae are ultra-sensitive to colony-specific chemical signals.

- Nasonov Gland: Found in workers, releases a pheromone to guide bees back to the hive.

Visual Anatomy (Suggested Graphic Sections)

If you’re adding visual content, include:

- Labeled diagram of honey bee external anatomy.

- Cross-section showing internal systems.

- Comparison of queen, worker, and drone anatomy.

Let me know if you’d like these images generated or inserted.

Conclusion

The anatomy of a honey bee is an extraordinary example of evolutionary design. Every organ, appendage, and sensory structure serves a specific purpose in supporting the hive’s complex social structure. Whether you’re a beekeeper, student, or enthusiast, understanding bee anatomy enhances your appreciation and ability to care for these essential pollinators.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the function of a honey bee’s proboscis?

It is used to suck up nectar and water during foraging.

Q2: Do all bees have stingers?

No. Only female bees (workers and queens) have stingers. Drones do not.

Q3: How do bees breathe without lungs?

They breathe through spiracles that connect to a network of tracheal tubes.

Q4: What is a pollen basket?

It’s a concave area on a worker bee’s hind legs used to store and transport pollen.

Q5: Why do worker bees die after stinging?

Their stingers are barbed, and when they sting, the stinger remains in the skin, causing fatal internal damage.

Q6: What makes queen bees anatomically different?

They have fully developed reproductive organs and longer abdomens, with smooth stingers.

Q7: How big is a honey bee’s brain?

Very small—about the size of a sesame seed—but capable of complex behavior and memory.

Q8: Can bees see color?

Yes, bees can see ultraviolet light and a wide range of colors, especially those that guide them to nectar.